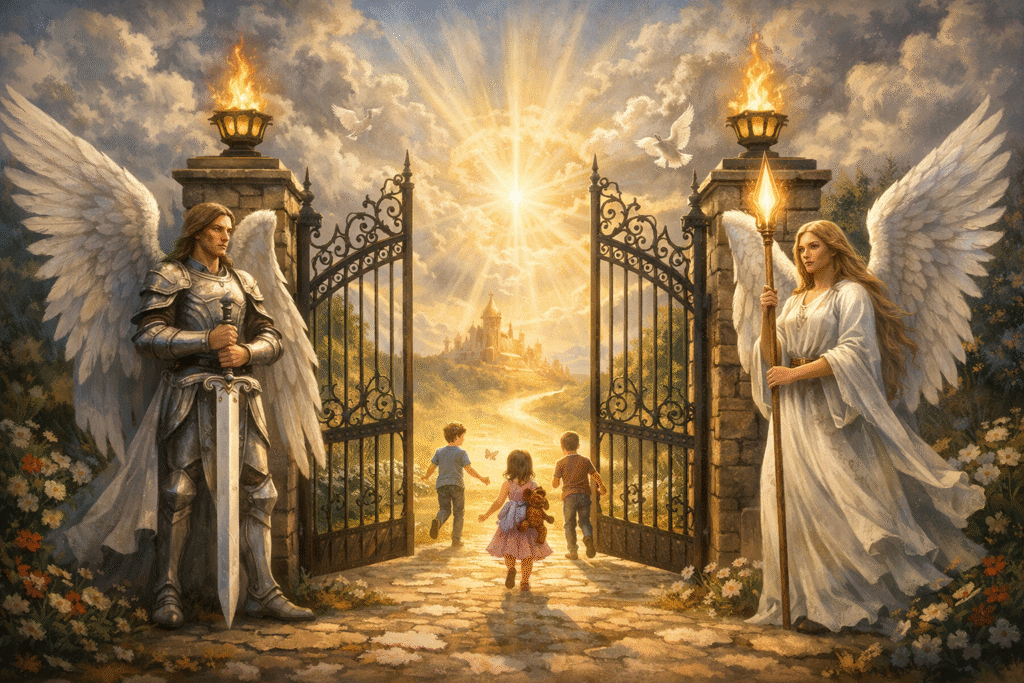

Guarding the gates of children’s souls

Every civilization is remembered not by its monuments, but by the souls it forms. And the soul is formed first not in the marketplace, nor even in the schoolroom, but in the quiet, hidden places of the home. There, long before a child learns to argue, he learns to imitate; long before he reasons, he absorbs. Thus, the greatest influence upon a child today is not the teacher, the politician, or the priest—but the unseen tutor glowing silently in the corner of the room.

In past ages, parents worried about bad companions at the door. Today, the companions have already entered the living room.

We live in an age intoxicated with images. Never before has the human mind been so constantly addressed, so relentlessly stimulated, so subtly shaped. The modern child does not merely watch—he is formed by what he watches. For ideas have consequences, but images have instincts. They bypass reason and lodge directly in the imagination, where they quietly begin to tell the soul what is normal, what is desirable, and what is permissible.

The tragedy is not simply that children are exposed to evil, but that they are exposed to it without judgment. When a child is shown violence without justice, pleasure without responsibility, and power without virtue, he learns a lie about reality itself. He is taught that actions need not have consequences, that truth is negotiable, and that the highest good is personal satisfaction.

A child does not need to be taught to desire; desire comes naturally. What he needs is to be taught what is worthy of desire.

Parents are the first gatekeepers of the imagination. To abdicate this role is not neutrality—it is surrender. One cannot say, “The world will teach them anyway,” without admitting that the world is being trusted more than conscience. The home that refuses to form will inevitably be deformed by what it permits.

This does not mean that children must be raised in ignorance or fear. Shielding is not the same as sheltering. To moderate what children watch and learn is not to deny reality, but to introduce it gradually, truthfully, and morally—just as one teaches arithmetic before algebra, and walking before running. A soul, too, must grow in stages.

The question is not merely Is this entertaining? but What kind of person does this make my child become?

Does it teach reverence or ridicule?

Does it awaken compassion or dull it?

Does it glorify sacrifice or self-indulgence?

For every story carries a theology, even when it denies having one.

Parents must remember: children rarely rebel against rules; they rebel against inconsistency. When adults consume without restraint what they forbid their children, they preach a silent sermon of hypocrisy. But when a parent models discernment, self-control, and a love for truth, the child learns that limits are not punishments—they are protections.

True freedom is not the ability to choose anything, but the ability to choose the good.

The modern world will call this prudence “control,” and discipline “oppression.” But history will tell another story. It will show that civilizations fall not when children are taught too much morality, but when they are taught too little. When parents cease to be moral guides, the state, the screen, and the crowd will eagerly take their place.

In the end, the task of moderating what children watch and learn is not about censorship—it is about custody. The custody of the imagination. The custody of innocence. The custody of a future not yet spoken.

For if we allow the soul of a child to be shaped entirely by noise, novelty, and pleasure, we should not be surprised when, as adults, they find silence unbearable, truth offensive, and virtue inconvenient.

But if we guard the gates wisely, lovingly, and courageously, we may yet raise a generation capable not only of living in the world—but of redeeming it.